|

||||

| about | map | timeline | tour | resources |

|

||||

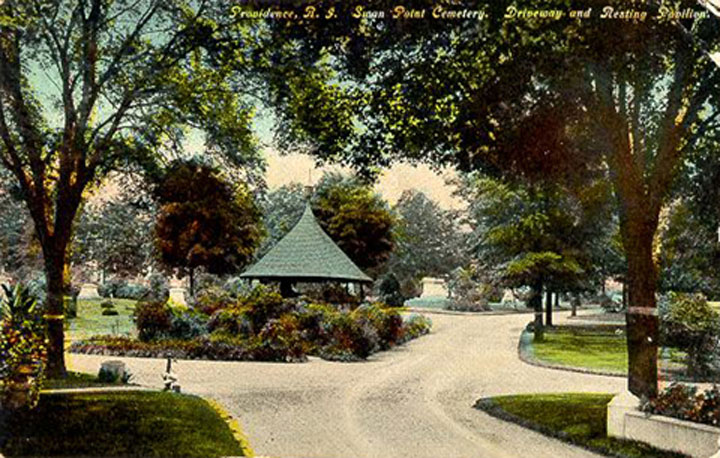

While many may find it unusual for a Los Angeles-based organization to interpret the history of a Rhode Island site, we hope that our methods have created an investigation that builds on the discipline's goals of showing change over time and place. The Studio's mission is to critically chronicle and disseminate local history in order to foster sense of place and civic engagement. Swan Point Cemetery is the final resting place for prominent politicians, religious leaders, artists and civil rights activists; we are optimistic that the information visitors explore here will teach them about the history of making Providence and the United States. Swan Point Cemetery is a memorial park in Providence, Rhode Island that was founded by Thomas C. Hartshorn in 1846. Its design is in line with the 19th century "rural cemetery" movement where cemeteries become public parks and places for contemplation and to visit. According to historian Thomas Bender:

According to the Rhode Island Historical Preservation Commission, the cemetery was designed after the concept of a "rural cemetery" in contrast to traditional New England cemeteries which are in the city. The rural cemetery reflected 19th century ideals connected to public health, spirituality, and nature:

Swan Point Cemetery is one of the most beautiful cemeteries in the United States, and several distinguished architects and planners contributed to its development including its original designer Niles B. Schubarth, Horace W.S. Cleveland, the Olmstead Brothers, Thomas A. Tefft (who is also buried here), James C. Bucklin, Alfred Stone, and John Hutchins Cady, in addition to generations of horticulturalists and local guardians. Swan Point served as a central burial site for Providence. In the late 19th century hundreds of bodies were re-buried here from the First Congregational Society, the West Burial Ground and original cemeteries from the Rhode Island colony and early Republic. On July 2, 1847 the grounds were consecrated with services conducted on "the eastern slope" by Reverend Nathan B. Crooker (Saint John's Episcopal Church); Reverend Samuel Osgood (Westminster Congregational Church); Reverend John P. Cleveland (Beneficent Congregational Church); and President Francis Wayland (Brown University) gave the dedicatory address. Music was provided by the Beethoven Society. "Pastor's Rest" was erected in 1850 to mark the remains of Reverend Enos Hitchcock (pastor for the First Congregational Society 1783 - 1803). Remains from the West Burial Ground were "widely scattered through the old portion of the grounds, with concentrated areas in the southeast section between Forest and Side Hill avenues, in the east section between Beach and Willow avenues, and in the west section bordering Prospect Avenue." Early rules for the cemetery revealed who, how, and when visitors came to Swan Point. 1847 rules included the following restrictions:

The plan for the cemetery was laid out following Andrew Jackson Downing's rules for landscape design which emphasized the "adaptation of man-made elements to the peculiarities of each site and the desirability of picturesque and naturalistic effects achieved through irregularity and asymmetry in structure and plantings." Places were named following nature: Forest Hill, Cedar Knoll, Sidehill Avenue, Laurel Way, Magnolia Path. As the tour shows, there are different leaders in the cemetery from art, civil rights, industry, military, politics and literary history. Additionally, Swan Point Cemetery contains memorials and the remains to both prominent and lesserknown Rhode Islanders. As history is source-driven, this investigation does not show a representative example of who is buried in Swan Point; rather, this study builds on what is available in published sources. There are undoubtedly many more compelling entries to add to this history and this site represents a beginning. In many ways, Swan Point Cemetery represents a microcosm of Providence history in both the residents and memorials here, and in the Cemetery's own history as an institution. It is still a receiving cemetery and there are plots available. Undoubtedly, interments from the twentieth century – demonstrating the diversity of Providence resulting from its waves of “new” immigration over the last hundred years – have yet to be documented. We look forward to seeing that history acknowledged in scholarship and at the Cemetery. |

||||

copyright 2012 |

||||